“Limited-time offer!”

“Everything must go!”

“This opportunity disappears at midnight!”

“Don’t miss out! Act now!”

Marketing like this is everywhere. But should everyone be doing this kind of marketing?

Loss aversion is a principle from psychology that’s captured the imagination of marketers.

Still... in the transition from intense psychology research to selling products, marketers have missed out on some of the important lessons the research teaches.

Don’t get me wrong — loss aversion is powerful. As we’ll see, it often makes sense to use some loss aversion in your marketing.

But there are questions that need to be answered:

- Should you always use loss aversion? Just how effective is it?

- What effect does loss aversion have on your brand (and long-term success)?

- How can you use loss aversion and still stay classy?

If you’re in marketing for any length of time, you’ll eventually have someone tell you to throw in some loss aversion. Add a countdown timer. Build some urgency.

This is when you should use loss aversion marketing — and when it might actually be harmful.

What is loss aversion?

Loss aversion is a psychological phenomenon in which people prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains.

Who discovered loss aversion? Nobel Prize-winning psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky discovered loss aversion during their research on Prospect Theory. The full Prospect Theory models how people make decisions.

In the course of their research, Kahneman and Tversky noticed something odd — people seemed to value a loss more than an equivalent gain.

Loss aversion examples

Here’s the scenario that Tversky and Kahneman presented in a 1981 study:

“Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

- If Program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

- If Program B is adopted, there is 1/3 probability that 600 people will be saved, and 2/3 probability that no people will be saved.

Which of the two programs would you favor?”

Think about that for a second while I show you the options shown to the other group of participants in the experiment.

“Assume that the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

- If Program C is adopted 400 people will die.

- If Program D is adopted there is 1/3 probability that nobody will die, and 2/3 probability that 600 people will die.

Which of the two programs would you favor?”

In the first group, most people picked Program A—they wanted to guarantee that some lives would be save.

But in the second group, most people picked Program D. Even though that option is identical to Program B, which people didn’t like.

Phrasing the decision in terms of deaths instead of lives saved made people change their choices. They didn’t want to lose lives.

In other words, they were loss averse.

The concept of loss aversion has since been studied in a bunch of other ways too.

One famous study, which I’ll call “the mug study,” found that people valued objects they owned more than objects they didn’t own — even if the objects were exactly the same.

If you give me a mug from the campus bookstore (one of the objects studied), then offer to buy it back from me, I’m going to charge you a high price — notably, a price higher than the cost of me just buying a new, identical mug.

This is the “endowment effect,” and is one way that loss aversion can manifest itself “in the wild” (aka, outside of a lab).

Try it now, for free

How is loss aversion used in marketing?

With mugs and catastrophic diseases behind us, we have a sense of what loss aversion is. But where do marketers use loss aversion?

The answer? Everywhere.

Check your inbox — if you’re on the marketing newsletter for any brand, you’re sure to have some “LAST CHANCE TO BUY” emails in there.

Watch TV. In between reruns of How I Met Your Mother, check the commercials for “limited-time offers.”

Landing pages have countdown timers at the top of the page, to remind you that this offer disappears soon.

A landing page countdown timer

Online courses have a deadline — doors close on Friday at 11:59 pm! Last chance to join! Here’s a countdown timer used in a recent Ramit Sethi email for his course Ready Set Evergreen:

Once you start looking for loss aversion, you start to see it all over the place. Marketers are addicted to it.

And, sometimes, it gets incredible results:

Source: Marcus Taylor on ConversionXL

Marketers face a huge challenge. A simple, everyday concept that brutally murders sales and conversion rates.

“Tomorrow.”

As long as someone thinks “I can always do this tomorrow,” they have absolutely no reason to buy from you.

That’s why so many marketers rely on urgency, the scarcity principle, and loss aversion to sell products. A prospect waiting for “tomorrow” isn’t actually saying no to your offer — there’s choosing not to make a decision at all.

When you can make someone feel the pain of not taking action (with loss aversion), you can help them make a decision. And those decisions can help you increase conversions.

When you use urgency to sell, you take tomorrow off the table altogether.

Loss aversion is a powerful psychological fundamental. People feel losses more deeply than they feel gains. Loss aversion can get them to move when they would normally stand still.

But there’s a problem...

The dangers of marketing with loss aversion

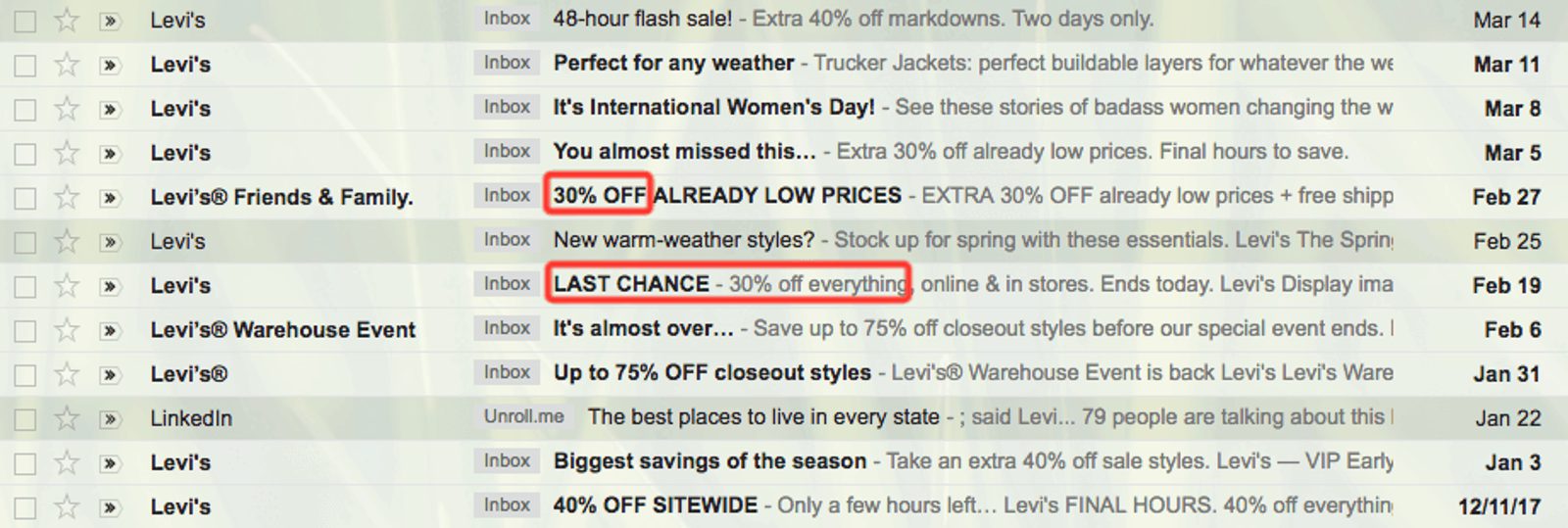

I get a lot of emails from Levi’s. In their defense, I love their jeans. I just don’t care for their emails.

Check it out: On February 19th, they told me it was my LAST CHANCE to get 30% off…

But just 8 days later on February 27th, I could get 30% off again?

On March 5th they say that “You almost missed this…” and that it’s the “final hours to save.”

But then on March 14th, there’s a two-day sale for 40% off.

I know not all of these sales are necessarily for the same products. Although it only took them until March 29th to offer another sitewide sale for 30% off.

The problem with Levi’s marketing emails? I don’t believe them.

If you say it’s my last chance — excuse me, LAST CHANCE — to get 30% off... and then offer another 30%-off sale a week later... why would I take action on the first sale?

All Levi’s has done is ensure that I’ll never buy jeans at full price. I know there’s a sale coming, so I’m always going to wait for the next discount.

Expert insight: Margo Aaron

“People who over-use urgency dilute its effects. It's like walking past a store that says "LAST DAY – CLEARANCE! EVERYTHING MUST GO!" but the sign is still there the next day... and the next day... and the next day. Eventually people catch on.

– Margo Aaron started her career as a psychology researcher, then transitioned to become a digital marketing and copywriting expert. She writes at That Seems Important.

In a paper called The Boundaries of Loss Aversion, Novemsky and Kahneman point out that loss aversion only works when people believes there’s something to lose.

When I get bombarded by a slew of loss aversion marketing, I don’t believe any of them. So the loss aversion stops working.

The only thing that’s really happened is a decay of the brand. A loss of trust.

Neuroscience and loss aversion is still an emerging field, but some research shows that people with amygdala damage don’t experience loss aversion.

The amygdala is a part of the brain related to emotional responses, including fear and risk. This research supports the idea that its activation is part of what creates loss aversion.

I don’t want to jump to conclusions based on this research (it’s still young)... but if the amygdala is activating with every loss aversion message you send, over time your brand is going to become associated with fear and risk.

You probably don’t want that, right?

Armed with psychology and case studies about high conversion rates, using loss aversion in marketing seems safe.

But there are limitations to the research, and implications of the research not everyone considers. I don’t want to get too bogged down in journal articles, so here are some quick hits:

- Loss aversion hasn’t been studied over the month- and year-long timelines marketers care about (to understand long-term effects on branding)

- Most loss aversion research measures the effect of loss aversion using money. That doesn’t make the results irrelevant, but it’s worth keeping in mind that marketers don’t usually sell money.

- Any time you sell something, you’re fighting loss aversion — the aversion to spending money

- Loss aversion seems to be stronger for larger losses — and some research has struggled to find the effect for small losses

The most important insight, to me, comes from that same study about the boundaries of loss aversion.

Research shows that people don’t experience loss aversion when they are spending money that they have already allocated for specific purposes.

Similarly, if someone has decided to sell or get rid of an object, they don’t seem to experience the endowment effect.

What if, instead of hammering home loss aversion, you were to absolutely trumpet the benefits of your offer?

What if you could make people want what you had to sell so badly that they practically threw their money at you?

You could totally bypass their aversion to spending money.

Don’t just tell people what your offer does for them — paint them a picture of a life they can’t say no to.

As copywriter Robert Collier says in The Robert Collier Letter Book:

“The mind thinks in pictures, you know. One good illustration is worth a thousand words. But one clear picture built up in the reader’s mind by your words is worth a thousand drawings, for the reader colors that picture with his own imagination, which is more potent than all the brushes of all the world’s artists.”

When your prospects can imagine the life you show them, they activate loss aversion on their own.

If they can imagine the life strongly enough, the pain of not having that life is magnified. Loss aversion is working for you — but because you aren’t the one saying it, it doesn’t reflect negatively on your brand.

If Levi’s really wants to sell me jeans, all they need to do is use the subject line “Jeans you can squat in.”

I’d buy out their inventory in a heartbeat.

4 loss aversion marketing strategies (that actually work)

Have you ever added salt to a slice of pineapple, or a piece of chocolate?

If you haven’t, I strongly recommend you try it—a tiny pinch of salt has a way of bringing out the sweetness in the fruit, and the result is incredible.

But if you add too much salt, you’re just eating a salty pineapple.

Loss aversion should be used like salt on a pineapple. A pinch of loss aversion can make your offer that much sweeter. A bucket of it leaves people with a funny taste in their mouths.

When used the right way — and sparingly — loss aversion can be a great tool for conversion rate optimization. Here are a few ways you can get the conversion benefits of loss aversion without hurting your brand.

1. Sell benefits hard. Then push for a decision.

I’ve alluded to this idea a few times already.

Most consumers aren’t actively saying no to your offer — they’re choosing not to make a decision at all.

Loss aversion works because it builds tension. The tension between what people have and what they want to have.

Research shows that even imagining a making a choice creates an attachment to that choice.

If that’s the case, you can activate loss aversion without needing to include it in your marketing copy.

Copywriter Ry Schwartz makes this point extremely well in a blog post on Copy Hackers. If you’ve done the work of painting a better future in your prospect’s mind, you’ve earned the right to ask them a hard question.

Source: Ry Schwartz via Copy Hackers

When you ask someone to make a decision point-blank, there is no more tomorrow. They are faced with two possible futures:

- Their current life

- The ideal scenario you’ve painted for them

Loss aversion kicks in on its own. You’ll never have to say things like “don’t wait” or “you’re missing out.”

2. Use loss aversion without urgency

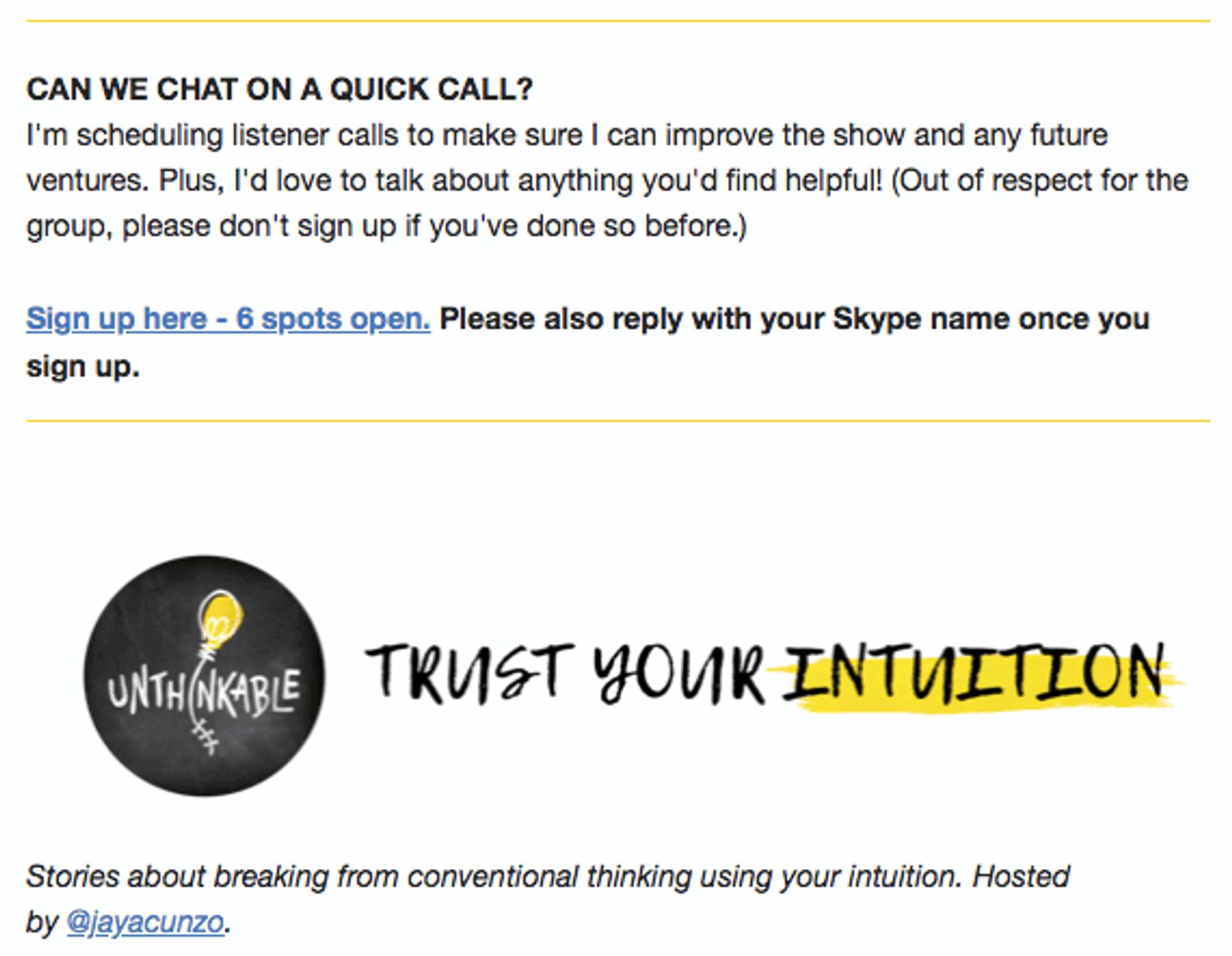

I’ve been on Jay Acunzo’s email list for a little over a year. Every so often he sends an email like this one:

Jay Acunzo has been a keynote speaker at Content Marketing World. He works with major brands. He’s a busy guy, and the offer of his time is very generous.

It’s also totally believable that he only has time for 6 calls. And that makes his offer all the more valuable — without reflecting negatively on him.

Another example: In 2016, Seth Godin created a limited-run coffee table book containing all of his blog posts. The book was over 800 pages long, and cost $400.

Source: Seth’s Blog

Godin was very clear that this was a project that he would only complete once. Because the book was a limited-run and highly exclusive, Godin was able to activate a feeling of loss aversion and use the scarcity principle to his advantage.

Creating that feeling increased sales and word-of-mouth for his book — without reflecting poorly on his brand.

If you have a legitimately limited stock, say so. Your messaging doesn’t need to be over the top — just tell people that supplies are running low, and you don’t know when you’ll have more. Scarcity principle without the

Simple loss aversion. Less brand blowback.

3. Make your loss aversion real

If you’re going to use loss aversion in your digital marketing, go all-in and make it believable.

If you want to run limited-time sales or offers, go ahead. But don’t run them constantly — and emphasize that they are infrequent.

If you want to use loss aversion on your landing page — do it!

But really work to make the loss aversion believable. Just adding “don’t miss” or “don’t wait” to your copy isn’t enough. You need to actually structure your marketing messaging around the pain of losing this opportunity.

We’ll see an example of that in our final loss aversion scenario.

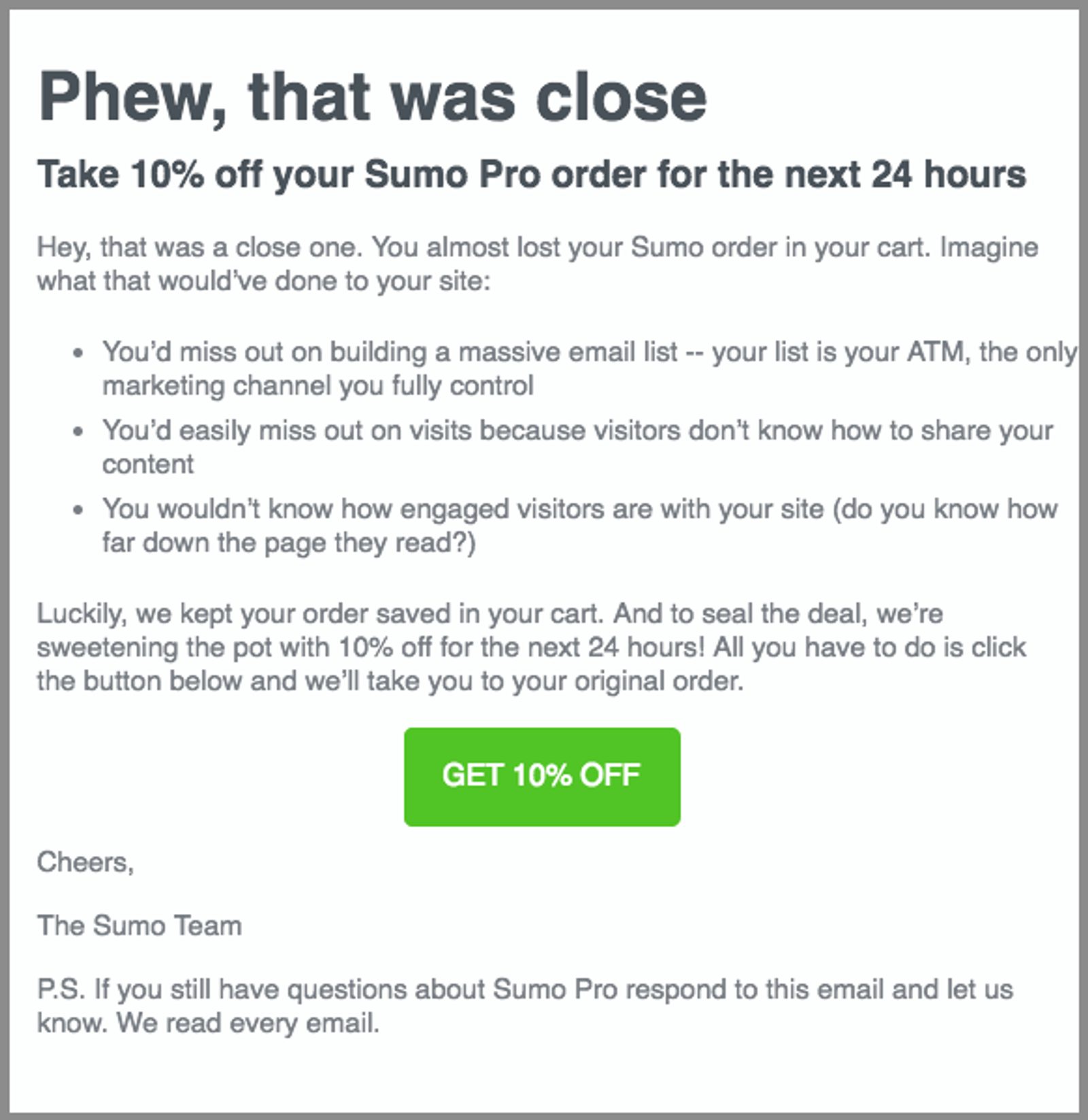

4. Abandoned cart emails: The best time for loss aversion

Abandoned cart emails are a fantastic time to go hard on loss aversion.

Why?

When a shopper places an item in a shopping cart, they’ve stated their interest in it. And although they haven’t bought anything yet, putting an item in an online cart is probably enough to activate the endowment effect.

In other words, there’s actually something at stake!

At this point, the shopper has come so close to making a decision. All they need is a little encouragement to get them to take the next step.

Take a look at this fantastic example from Sumo:

Source: Sumo, via Copy Hackers

Ooooooh boy! Can you feel the pain?

Sumo makes it crystal clear what you’re missing by not signing up for their service:

- A massive email list

- A marketing channel I can control

- My content spreading like wildfire

- Engaged visitors

All of that, capped off by a provocative, doubt-inducing question (“do you know how far down the page they read?”) and a small discount.

That’s what great loss aversion marketing looks like. It’s built into the foundation of this email copy. It goes way beyond telling you not to miss out and makes you crave the benefits of the product.

Conclusion: Loss aversion marketing

Remember, loss aversion is powerful. And to quote Uncle Ben from Spider-Man: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

I’ve come down pretty hard on loss aversion marketers so far, but the truth is that I’m a fan of loss aversion. You can use loss aversion to increase conversion rates and brand engagement through your marketing — if you use it strategically.

Understand how loss aversion works. Know when it applies and when it doesn't matter. Consider the risks. Use it like a scalpel instead of a chainsaw. Watch your marketing improve.